This post might be bit atypical because it deals with more math-y stuff than code-y stuff, but I’ve been learning a lot of cool math recently and really wanted to share it!1

So what is a ‘Hackenbush’? And why are we hacking in bushes?

Dots and Lines

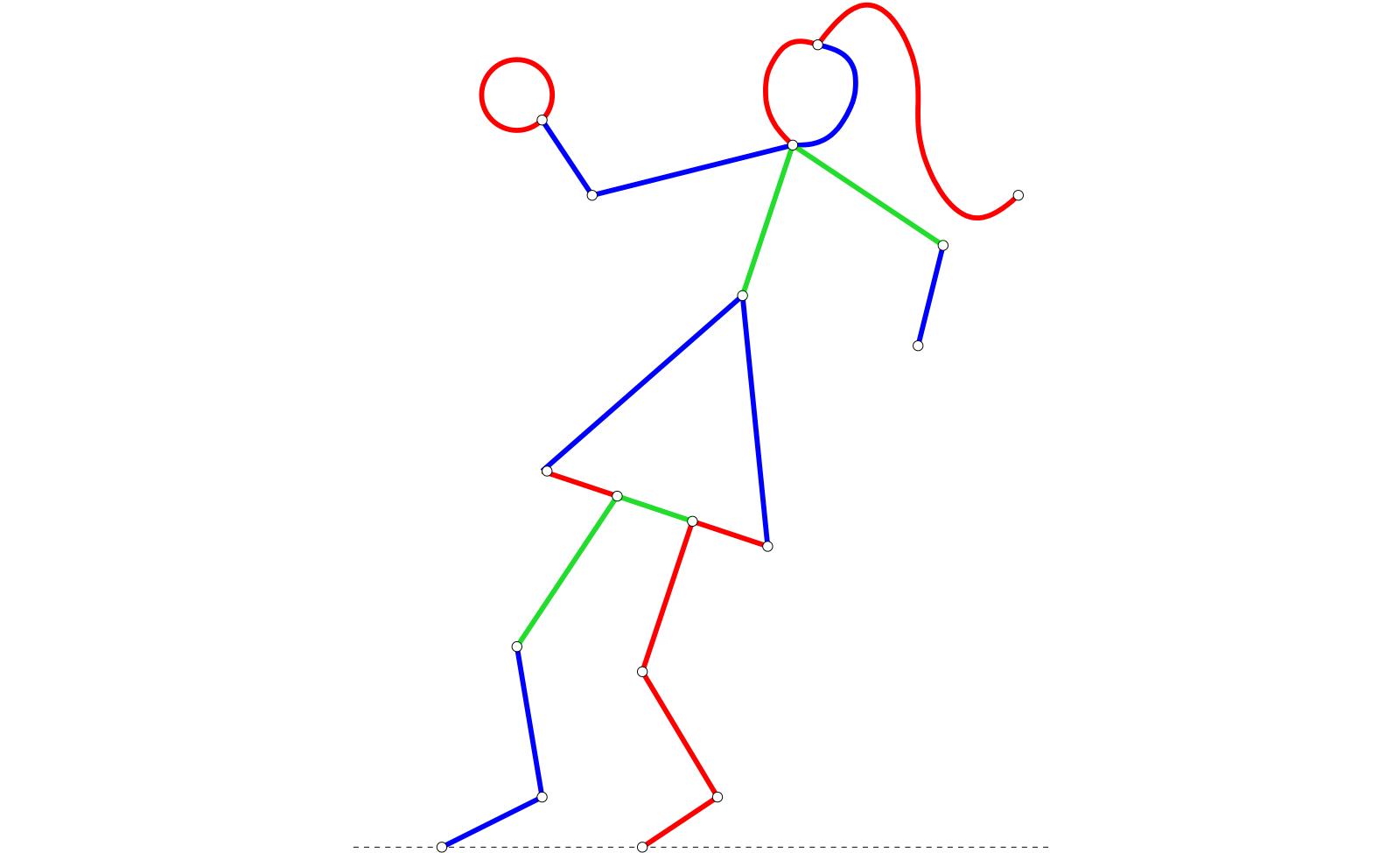

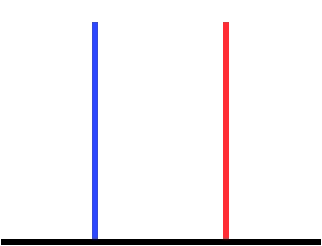

Hackenbush (or at least the Red-Blue version) is a game made by John Conway (of Conway’s Game of Life). It looks a little something like this:

You start with a ‘ground line’ and some red, blue, and green edges that are connected to the ground line. Two players, which we’ll call Left and Right, take turns ‘hacking off’ edges from the board. Left can remove blue edges, Right can remove red edges, and either player may remove green edges. Any edge that is no longer connected to the ground ‘falls off’ the graph, and the last player to make a move wins.

Hackenbush is an example of a combinatorial game – which basically means that it’s a two player, turn-based game where there is no element of chance. Think of chess, Go, tic-tac-toe, etc. And one thing that makes combinatorial games unique is that we should always be able to determine who wins if both players play optimally.

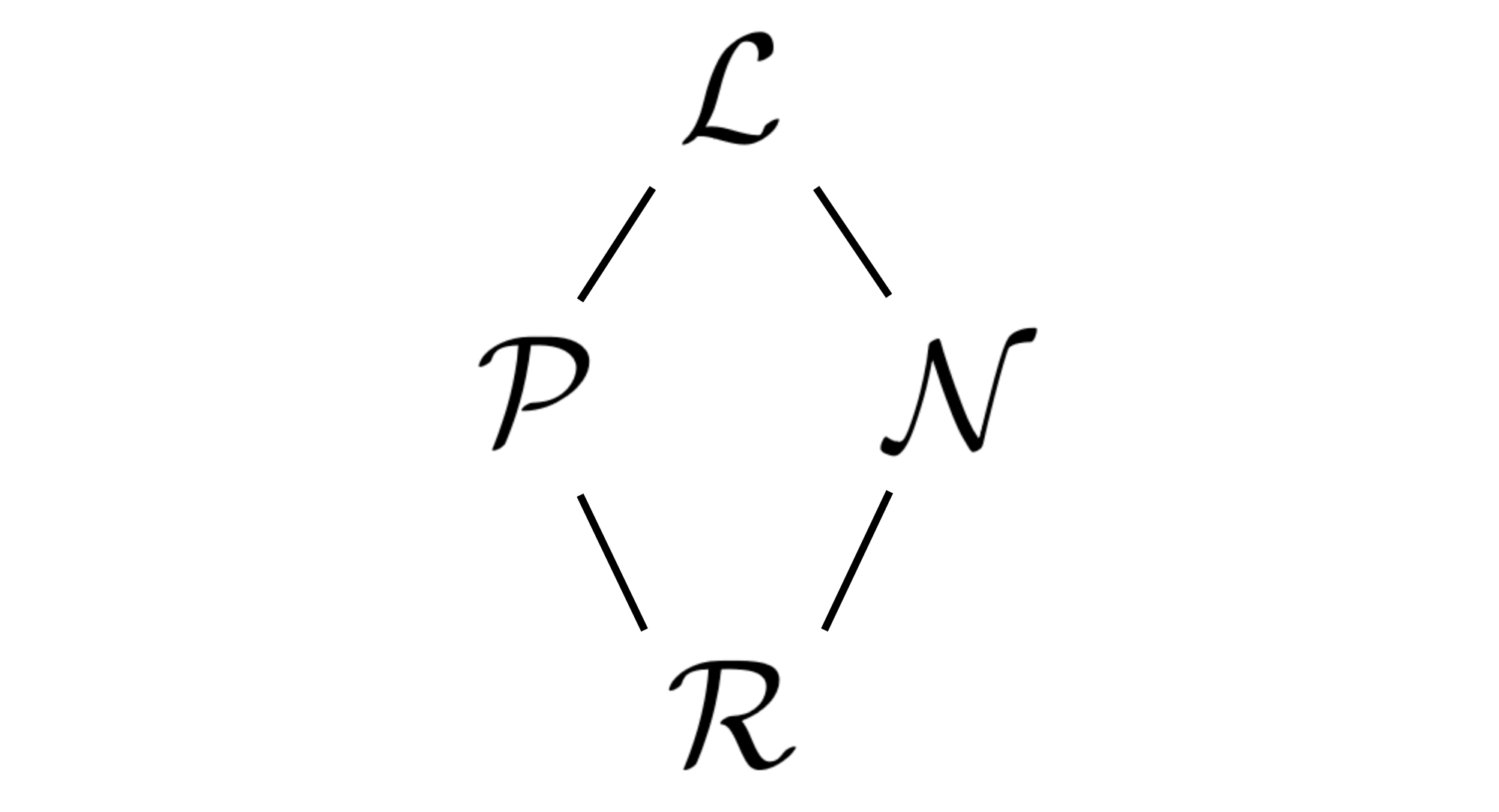

So who wins? There are four outcome classes that every Hackenbush game falls under, and here are some games to illustrate them.

Either we have that:

- Left always wins ($\mathcal{L}$)

- Right always wins ($\mathcal{R}$)

- The first player to move wins, or ($\mathcal{N}$)

- The second player wins. ($\mathcal{P}$)

These outcomes are called Positive, Negative, Fuzzy, and Zero, respectively, and you can think of them as being ordered by their favorability towards Left. Positive games are greater than Fuzzy and Zero games, and Fuzzy and Zero games are greater than Negative games, but Fuzzy games are incomparable with Zero games.

Now there’s a whole bunch of properties of games that we could go through, but the basic idea is that there are natural ways to add two games (put them next to each other), negate a game (switch the roles of Left and Right), subtract one game from another (from the two previous operations), and find whether two games are equal or not. So games have a very nice structure, and we can do arithmetic with them just like we can with numbers!

But I think the main thing I wanted to talk about is the value of games.

The value of games

The idea behind this is that we can assign a game a number by its move advantage towards Left. We write this as $G = \lbrace L \mid R \rbrace$, where $G$ is the value of the game, $L$ is the set of values of any move that Left could make, and $R$ the values of any move that Right could make.

So for example, the game with just one blue edge has a value of 1, since the ‘move advantage’ to Left is 1, and we write this as $1 = \lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace$ since Left can move to the game with no edges at all, and Right has no moves.

Here I think is where things get a little confusing, since it kind of seems like I pulled this notation out of nowhere (which is kind of how I first felt reading Winning Ways). What’s the point of writing things like this anyways?

The reason is that it lends itself to a natural recursive definition of a game. If $L$ is a set of games, and $R$ is another set of games, then $G = \lbrace L \mid R \rbrace$ is a new game where $L$ is the set of moves Left can make and $R$ the moves that Right can make. The base case is where both $L$ and $R$ are empty, which in Hackenbush would just be the ground line alone.

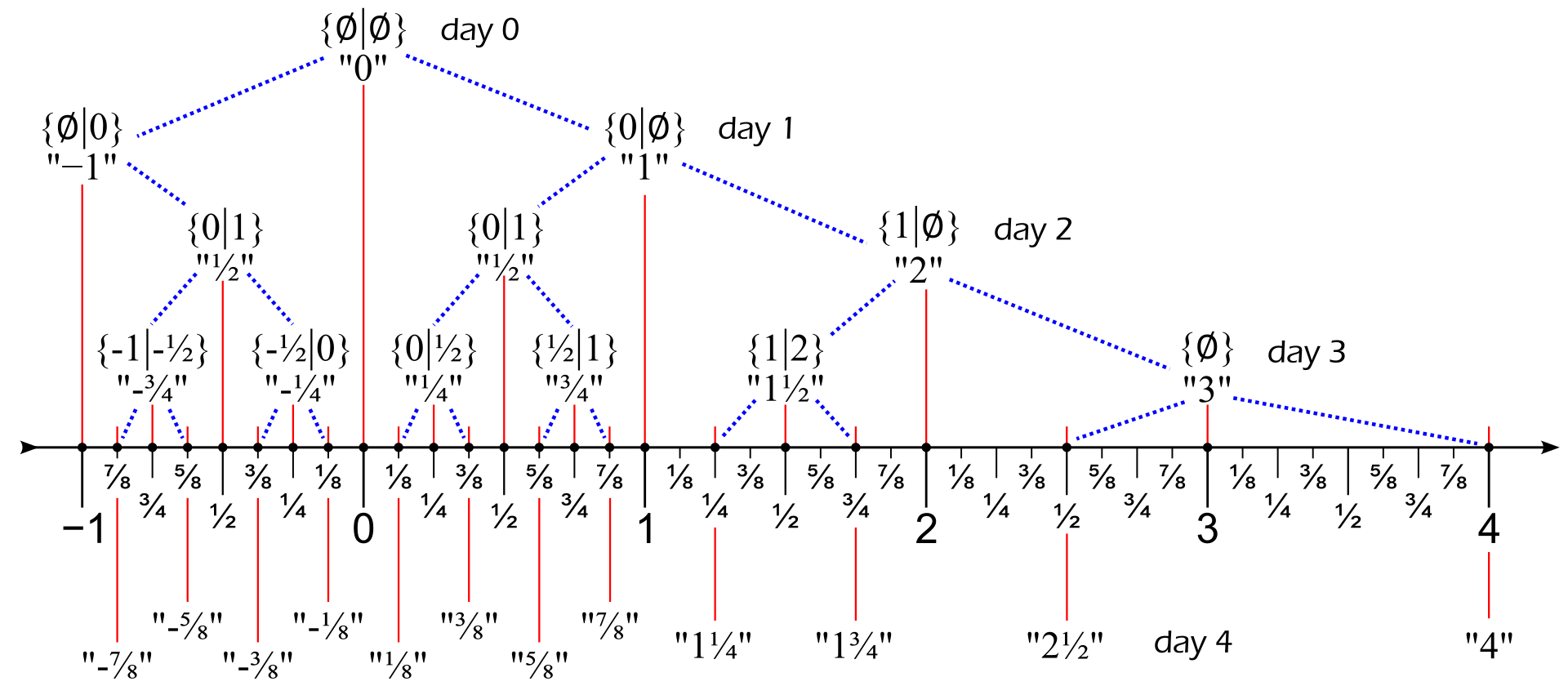

So on the zeroth ‘day’ of our recursive algorithm to create games, the game $0 = \lbrace \space \mid \space \rbrace$ is born.

On day 1, we can use $0$ on either of Left or Right sets, so the games $\lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace$, $\lbrace \space \mid 0 \rbrace$, and $\lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$ are born.

Since we order games by favorability towards Left, it’s clear that $\lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace > 0 > \lbrace \space \mid 0 \rbrace$ (since $\lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace$ is a Left-winning game, $\lbrace \space \mid 0 \rbrace$ is a Right-winning game, and $0$ is a second player win). So we’ll call these games $1 = \lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace$ and $-1 = \lbrace \space \mid 0 \rbrace$, respectively. What about $\lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$? It doesn’t really offer an advantage to either Left or Right, since the first person to play always wins. But it’s also not $0$ either! So we’ll call this game $* = \lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$.

And we can continue recursively creating more games with these new games until we have the set of all Hackenbush games (probably)!

For now though, we’ll limit our study to the Hackenbush games that are numbers (so excluding games like $*$). What can we say about these?

Numbers

First off, what makes a game a number? If we look at the games $\lbrace 0 \mid \space \rbrace$, $\lbrace \space \mid 0 \rbrace$, and $\lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$, we know that the first two are numbers and the last one is not. Why is that?

The reason goes back to the 1970s to the original construction of the surreal numbers by John Conway. Apparently when Conway was studying the Go endgame, he realized that typical Go endgames could be decomposed into sums of games as described above, and this idea led to the discovery of the surreal numbers as one of the structures for which this sum applies2.

The construction of the surreal numbers begins as follows:

Let $L$ and $R$ be two sets of numbers such that no member of $L$ is $\geq$ any member of $R$. Then $\lbrace L \mid R \rbrace$ is a number.

Now you might be a bit skeptical since we define what a number is using two sets of numbers – isn’t that kind of circular? It is a recursive definition, but we don’t have to define a base case because there already is one: the number where $L$ and $R$ are both the empty set. Since the empty set has no members, it isn’t possible for any member of $L$ to be $\geq$ any member of $R$, so $\lbrace \space \mid \space \rbrace$ is a number! And since it’s the ‘first number’ we can create, we’ll call this number $0$.

Because the empty set is kind of special in that we can use it to ‘vacuously’ prove any statement about members of a set, we know that any $\lbrace L \mid R \rbrace$ where either $L$ or $R$ is the empty set is also a number!

So you get a natural representation of the integers by letting $k = \lbrace k - 1 \mid \space \rbrace$ and $-k = \lbrace \space \mid -(k - 1) \rbrace$, and you can think about the ‘day’ that each number is born as the ‘iteration’ of the recursive algorithm that creates the number.

It turns out that with this construction, you can make all of the integers, rationals, reals, and even things that aren’t real numbers like infinite numbers and infinitesimals!

Numbers in Games

This construction of the numbers gives us a definition for which games are numbers: the games where all the Left options are strictly less than all the Right options. So something like $\lbrace -1 \mid 1 \rbrace$ is a game, but not $\lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$ because $0 \nless 0$. What does this mean in practice?

Essentially, there has to be a disincentive to move for both players: on moving, each player’s position will always become worse. Since we think about the value of games in terms of Left’s move advantage, this means that the value of the game decreases when Left moves, and increases when Right moves. So the value of the game itself lies strictly in between the values of its Left options and Right options.

For Hackenbush, only the games with no green edges obey this rule (since if there were a green edge, it could be removed by either Left or Right, giving us a game in Left’s options with the same value as a game in Right’s options, which breaks the ‘strictness’ we wanted!)

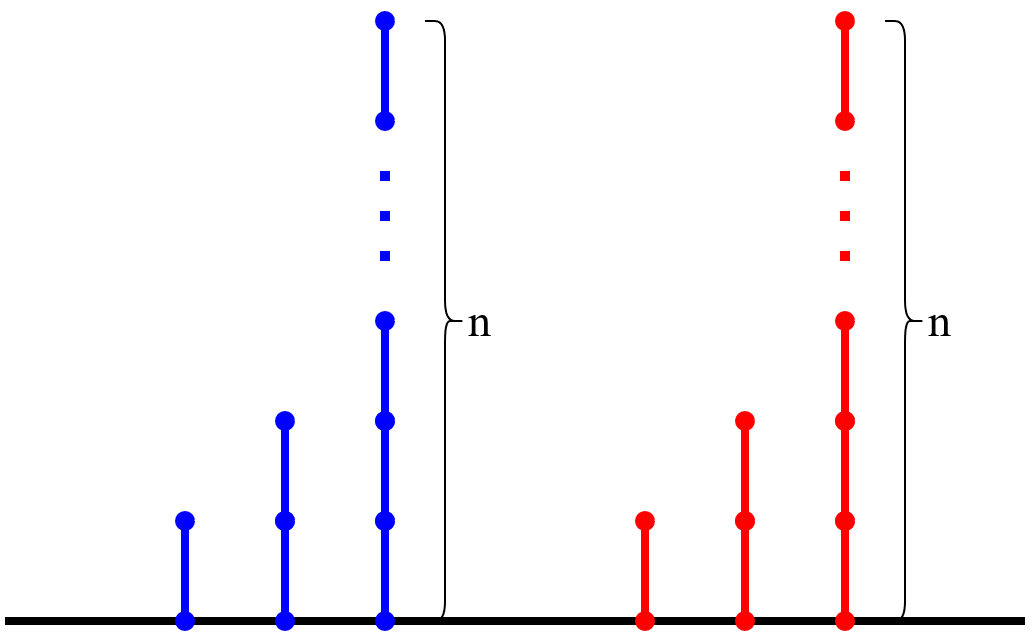

For the integers, it’s easy to make Hackenbush games with those values: a blue stalk with $n$ edges has a value of $n$, and a red stalk with $n$ edges has a value of $-n$, and we can write this as $n = \lbrace n - 1 \mid \space \rbrace$ and $\lbrace \space \mid -(n - 1) \rbrace$, respectively.

How do we actually calculate these values in general though, given an arbitrary game like $\lbrace -1, -2, 0 \mid 1, 3 \rbrace$?

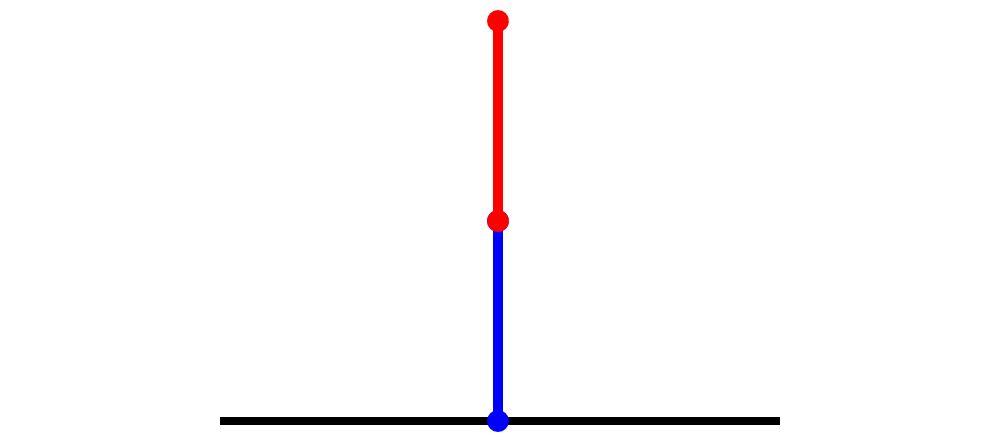

Well, since the value of the game has to be strictly in between the Left and Right sets, we really only have to worry about the greatest Left option and least Right option. So this simplifies to $\lbrace 0 \mid 1 \rbrace$, which you can visually think about as a Hackenbush game with one red edge stacked on top of one blue edge.

What value does this have? It has to be between 0 and 1, so should we call it $\frac{1}{2}$? It turns out that if we play two of this game versus one red edge (i.e. $-1$), we get a second player win. So it would certainly make sense to call this game $\frac{1}{2}$, since this gives us that $\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{2} - 1 = 0$. We can generalize this to the following rule:

Simplicity Rule – If a game $G = \lbrace L \mid R \rbrace$ is a number, then the value of $G$ is the simplest number greater than $L$ and less than $R$, where the simplest number is:

- the smallest magnitude integer between $L$ and $R$ if there is one, or

- a fraction of the form $\frac{i}{2^j}$ between $L$ and $R$ with the smallest $j$ possible

These are the dyadic rationals – rationals with powers of two as the denominator – and this gives us a way to calculate the value of any arbitrary Hackenbush game! We just have to look at every option that Left or Right could take, calculate the values of those, and find the simplest number in between them. Now this is actually very hard in reality, and calculating Hackenbush values in general is NP-hard (not good!).

To infinity and beyond

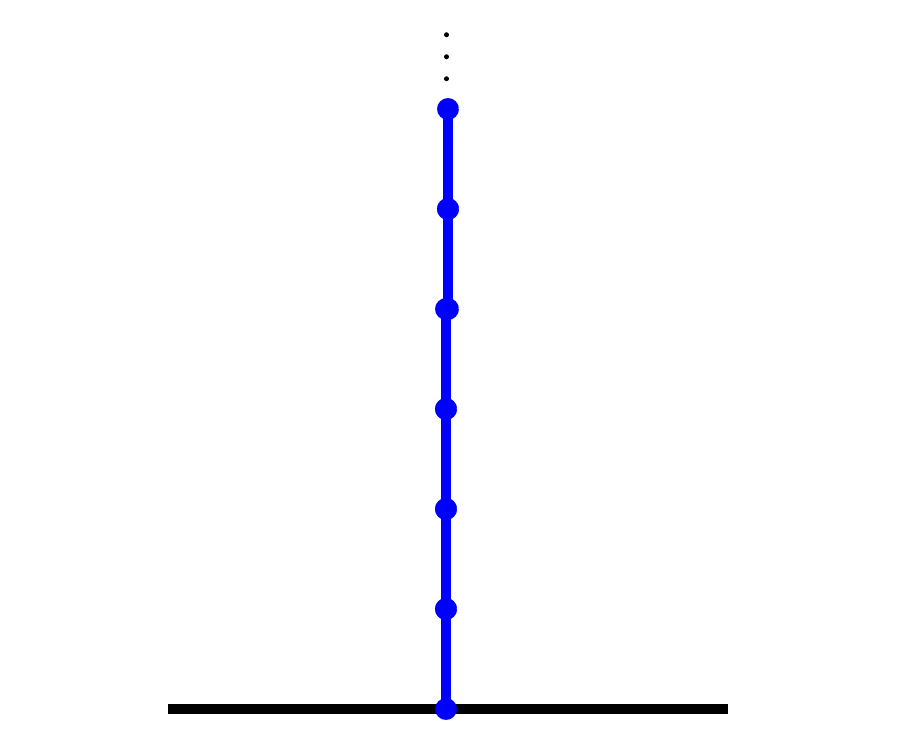

So far, we’ve only talked in detail about a small number of Hackenbush games. But the rules for Hackenbush are much more lax than the games that we’ve seen so far – like what if we had a Hackenbush stalk with an infinite number of blue edges?

This is definitely bigger than any of the integers since it goes on forever, so we’ll say this game has a value of $\omega$, for ‘infinity’. If we stack two of these on top of each other, we get $2\omega$, or if we just put one extra blue edge on top of it, we get $\omega + 1$ and all sorts of other weird infinite numbers!

What about games with green edges, like the game with just one green edge? In the notation we introduced previously, this is $\lbrace 0 \mid 0 \rbrace$ since both Left and Right can remove the green edge and get to the zero game, and we know this isn’t a number since $0 \nless 0$. So we’ll call this game $ * $. What about $* + *$, the game with two separate green edges?

The second player will always win this game, so $* + * = 0$, and $ * $ is its own negative! And if we call a green stalk with $n$ edges $ * n$, we can see that $*n + *n = 0$ as well! In fact, any pair of equal length green stalks will always cancel each other out, since the second player can just copy whatever move the first player makes on the other stalk.

These ‘star’ numbers are called the nimbers from the game Nim, and it turns out that addition with nimbers behaves just like bitwise XOR if we convert the length of each green stalk to a binary number.

and more!

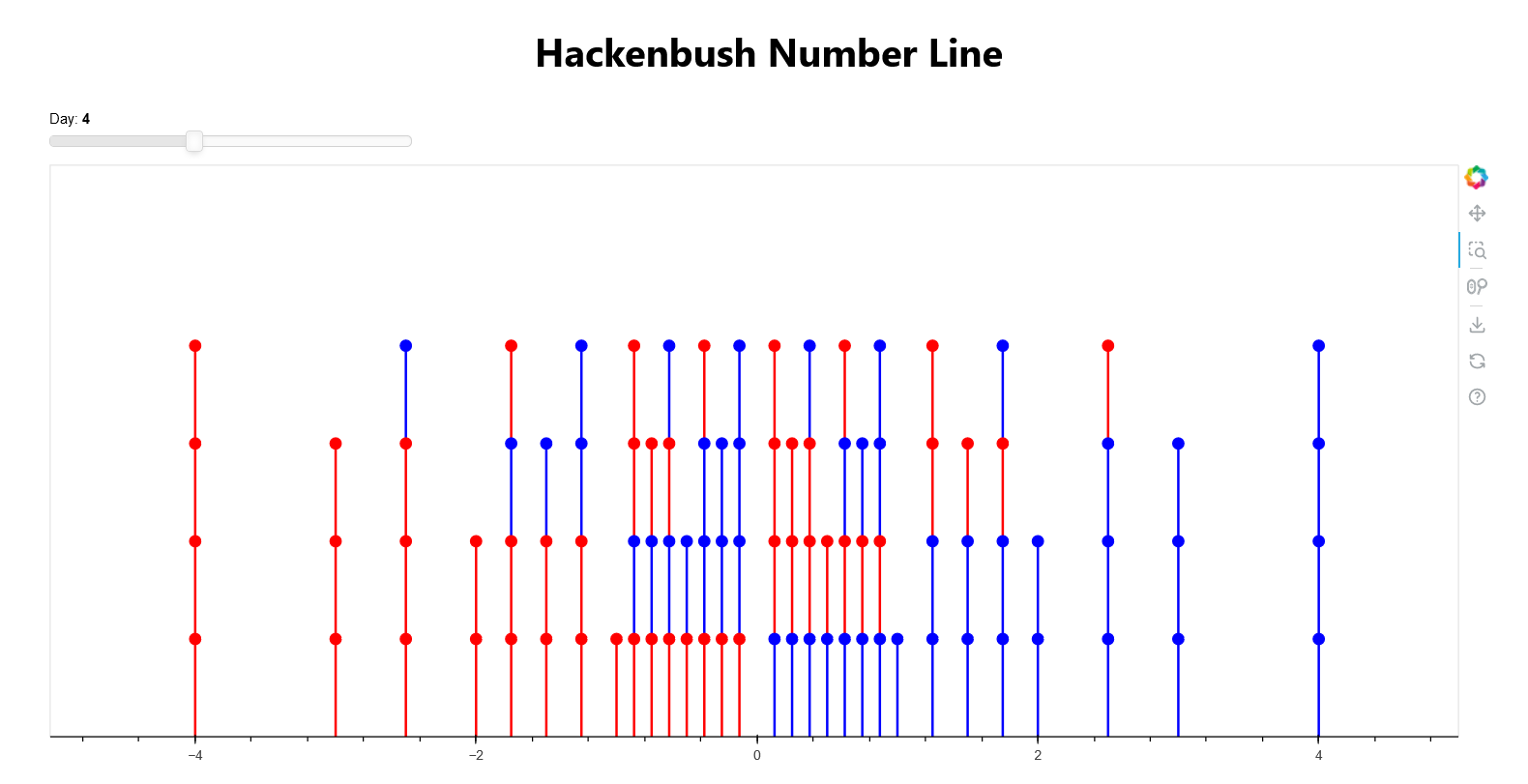

This post is adapted from a paper that I wrote as a final project for my Combinatorics class. It goes into a little bit more detail of the math behind combinatorial games, and if you’re interested you can read it here (fair warning – this was written in a state of delirium over a very short period of time and probably has several typos). As part of the project, I made a little visualization of Hackenbush stalks as numbers that you can find here (and here’s the source code).

It show which numbers on the number line are ‘born’ by which days, and the Hackenbush stalks that correspond to those numbers.

If you’re interested in reading more about the surreal numbers, I highly recommend Donald Knuth’s book Surreal Numbers. It’s a fairly easy read and takes you along the journey of creating the surreal numbers in a natural way. And it’s fun! Very untextbook-like.

I also recommend Winning Ways for your Mathematical Plays, by Berlekamp, Conway, and Guy. It’s another pretty easy read and talks more about different combinatorial games (and also more about Hackenbush)! The math is also not too math-like in here too, so even if you’re not a ‘math person’ I think you’d still enjoy it.

-

shoutout to Combinatorics and Dr. Hamaker ↩

-

While researching this theory, I found this passage in his book On Numbers and Games:

“I had long intended to see what would become of the theory when this restriction was dropped, but only got around to doing so when the then British Go Champion became a member of the Cambridge University Pure Mathematics Department.”

So I looked up the British Go Champions to see who the originator of this theory might be, but it turns out he was just being a little silly and was referring to himself (I think). ↩